Surprise! (I know I said I was taking time off, but this is something that I already had written, so it doesn’t count.) I’ve brought you the greatest gift of all: e-mail. 🎁

For my present to you, reader, I’ve un-paywalled this post originally written for Patreon in December of 2023. In it, I describe some significant changes that the final act of What Manner of Man underwent in the writing process (some of them live while it was being published, to my chagrin) with a few festive holiday detours to discuss A Christmas Carol, Christmas ghosts in general, and Apocalypse.

(Brief note to say that I’ve made a few changes to the original post for clarity, but it still contains various unedited references to things that were happening a year ago! I don’t want anyone to get confused.)

Did you know that, historically, it was Christmas that was the haunted holiday, rather than Halloween? From where I’m standing — deep in the dark season, when the night creeps so early that it can be hard to make it out of the house in time to catch a glimpse of daylight — it’s easy to see why. Ghosts pair nicely with the cold, lightless months when the night has gnawed and eaten away the day to almost nothing; the season of death. (I always go a little bit insane in December.)

It’s in this darkness that the old year dies and the new one is born. It is extremely appropriate, therefore, that we’re headed for the end of What Manner of Man — almost one full year after it began. (I might as well admit that I didn’t expect it to run this long — various things got a bit out of hand, as things are wont to do.)

And what, after this death, will be reborn from the ashes? Well, patron, I have plans (imagine I’m smirking and rubbing my hands together, here, like a wicked royal advisor,) but I am obliged to keep them secret for a little while longer. For now, let’s talk about endings.

Most of you probably recall that I took August (2023) to revamp the ending of What Manner of Man. It was urgently needed, and I hope that I have rewarded your patience with me.

What makes the climax of this story so powerful, I think, is that Victor’s refusal to follow his narrative to its inevitable conclusion has an even greater significance than is immediately obvious from the text. This is due to being a very late change to the story. The original ending gave a lot more — for lack of a better word — validity to the curse. In that version, the act of returning the ring to Lord Vane simply ended it.

What that means is that the final-but-one twist of the novel — where Victor exhorts Alistair to defy natural and divine laws, to break the trajectory of the narrative they’re on, (and possibly to kill God?) — is Victor actually reversing the original textual ending.

This last-minute decision transformed, to a significant extent, the meaning of the story as a whole. While the old ending was perfectly functional from a storytelling point of view, it meant, I’ve come to feel, that the book amounted to some fun but, ultimately, kind of meaningless pulp. The new ending weaves together the threads of anti-authoritarian subtext, turning the whole novel into what is, I'd like to think, a manifesto of disobedience.

The shift in perspective from Victor to Silas was another late addition.

In the version of the text where the reader remained in Victor’s point of view, I strongly suspected that the intensity of the emotions involved in this last action sequence blew past operatic into the realm of self-parody. Adding that little bit of distance — and the touch of ambiguity it brings — means that all of the heroism and tragedy and romance of the sequence isn’t dictated to you. At that stage of the story, the characters’ motivations and feelings are well-defined enough that it’s easy to fill that void yourself. It’s the same principle as never showing the monster — whatever you imagine will have more impact because you imagined it

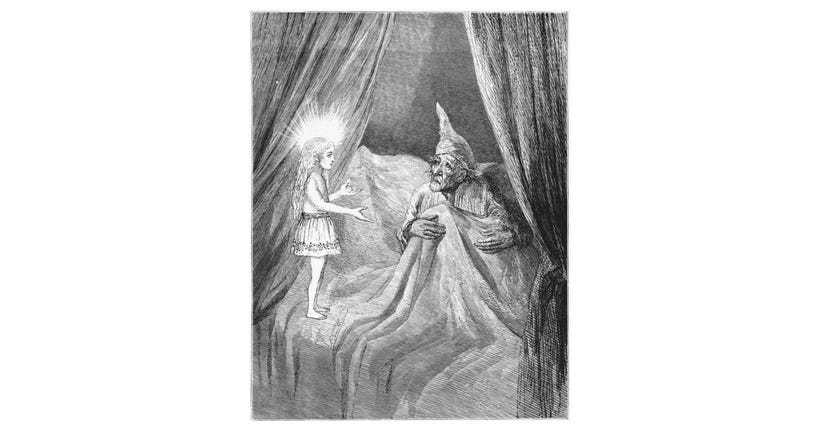

(Sol Eytinge Jr. illustration, A Christmas Carol, 1869)

Speaking of showing the monster — I settled on describing Lord Vane’s changing appearance and monstrous transformation as “flickering” as if seen “by the light of a guttering candle.” In doing so I reminded myself of a favourite seasonal ghost of mine: the Ghost of Christmas Past from A Christmas Carol. I enjoy the way the ghost has a bit of a Biblically accurate angel thing going on — with white hair, a white gown, and explicitly no gender. Strictly they/them, which has made for both some interesting and some extremely boring¹ choices in film and stage adaptations.

(LEFT TO RIGHT: Ann Rutherford in A Christmas Carol, 1938; Michael Dolan in A Christmas Carol, 1951; Edith Evans in Scrooge, 1970; Egg Muppet [performed by Karen Prell; voiced variously] in The Muppet Christmas Carol, 1992)

The ghost has, simultaneously, several arms and no arms, several legs and no legs, etc. Youthful, feminine beauty and the iron-pumping biceps of a bodybuilder. Goals, etc.

It was a strange figure—like a child: yet not so like a child as like an old man, viewed through some supernatural medium, which gave him the appearance of having receded from the view, and being diminished to a child's proportions. Its hair, which hung about its neck and down its back, was white, as if with age; and yet the face had not a wrinkle in it, and the tenderest bloom was on the skin. The arms were very long and muscular; the hands the same, as if its hold were of uncommon strength. Its legs and feet, most delicately formed, were, like those upper members, bare. It wore a tunic of the purest white; and round its waist was bound a lustrous belt, the sheen of which was beautiful. It held a branch of fresh green holly in its hand: and, in singular contradiction of that wintry emblem, had its dress trimmed with summer flowers. But the strangest thing about it was, that from the crown of its head there sprung a bright clear jet of light, by which all this was visible; and which was doubtless the occasion of its using, in its duller moments, a great extinguisher for a cap, which it now held under its arm.

Even this, though, when Scrooge looked at it with increasing steadiness, was not its strangest quality. For, as its belt sparkled and glittered, now in one part and now in another, and what was light one instant at another time was dark, so the figure itself fluctuated in its distinctness: being now a thing with one arm, now with one leg, now with twenty legs, now a pair of legs without a head, now a head without a body: of which dissolving parts no outline would be visible in the dense gloom wherein they melted away. And, in the very wonder of this, it would be itself again; distinct and clear as ever.

(Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, 1843)

(Sol Eytinge Jr. illustration, A Christmas Carol, 1869)

So, as I was saying before, Christmas (in the UK, at least) was traditionally the season of ghosts and ghost stories, something that’s been largely sidelined in the culture outside of remnants like A Christmas Carol. I think we urgently need to bring it back, quite frankly.

"Yeah, well, that’s exactly what you would say, St John," I hear you saying. You have astutely noted, perhaps, that What Manner of Man contains a serious amount of DNA taken from M. R. James, whose ghost stories for Christmas are still a popular yearly BBC tradition and an indispensable part of December in my household.

(Sol Eytinge Jr. illustration, A Christmas Carol, 1869)

The final chapters of What Manner of Man are more than a little apocalyptic — partly in the sheer scale of the destruction involved, yes, but also in the sense of it being a point of no return. Given the subject matter of the novel, it felt only right to give it an appropriately biblical ending.

I have, therefore, been thinking about the apocalypse in a broader sense, as well. The concept of the apocalypse creates a purpose to history; a meaning. It transforms history from something shapeless and largely cyclical into a thing driven by a force towards an ending — much like a story.

(You might say that all stories are, by their nature, apocalyptic.)

The apocalypse implies, however, a finality that doesn’t quite fit this story that has with its heavy pagan influence; whose structure has followed (however unintentionally) the course of the year. Years are bound to the cycles of the natural world, turning of seasons, etc. — so what kind of ending is correct for a story like What Manner of Man? Like I said, I have plans (😈) but best to keep them under wraps for now.

Finally — as a thank you for everyone's input into the concept sketches — here are a few bonus bats:

¹ (The most boring choices inevitably depict a normal blonde woman dressed like a Christmas tree angel. Boo hiss etc.)