What Manner of Man: Chapter 4 🦇

Out of the gay frying pan, into the gay fire.

LETTER TO VERA ARDELIAN

Dated March 1, 1950.

Dearest Sister,

Delivered at last — and in so dramatic a fashion! (As I have all along suspected, there proved to be an explanation for Lord Vane’s late appearance and I was met with many handsome apologies.)

Just as I had all but given up hope and was preparing to leave; he came. Lord Vane arrived on horseback — you can hardly imagine how he looked. He was like some darkly heroic figure straight out of tales of adventure; larger than life, burning with ferocity. He has a presence like thunder; I had no idea there were such men in the world — but I see I’m becoming imaginative.

Suffice it to say the impression he made upon me was immediate and electrifying.

Lord Vane towered over me, seated high on the powerfully-built animal that bore him; lean of body with hair black as obsidian, set ablaze by the dying dregs of the sun. He was dressed in exquisitely-cut riding clothes (though perhaps a little old-fashioned) — all black but for a ‘V’ of white shirt and collar at the breast. There was something of the crow about him, or magpie; in the sly, playful expression of his mouth and the elegant upward sweep of his brow.

He dismounted with ease and greeted me warmly, “Father Ardelian, my dear man!”

I reached out a hand and he clasped it warmly in both of his own. “You must be Lord Vane,” I said, “I’ve heard quite a lot about you.”

“All the worst kind of gossip, I’m sure — and entirely my own fault. I have just come from the docks where I learned that you have been here ever since the seventh! There must have been some strange mix-up, I was sure I had arranged for you to arrive today. What a monster you must think me.” Here a note of sweet earnestness entered his voice. “I’m so sorry to not have come sooner — do you despise me?”

What was I to say, Vera?

“How could I despise a man who rides so marvelously?” I smiled.

“Good man!” he beamed approvingly. “Tell me, do you ride?”

“Not since I was a boy.”

“That’s more than enough. I’ll keep you steady. Come, it’s growing late; let me take you to the Hall.”

Luckily my bags were all but packed and I wasted no time in fetching them. My one regret is that I had no opportunity to adequately thank the ladies who have been my hosts, for neither Danny nor Sylvia was present as I took my leave. In the flurry of departure, I left behind only a hastily-written note of thanks on my pillow. So impressive was Lord Vane’s entrance that I quite failed to notice when Sylvia — whom I’d been in conversation with at the time — had made an unobtrusive exit. (Perhaps in pursuit of Turnip, who had been frightened suddenly just before and had scratched me as he fled.)

When the time came to leave, Lord Vane lifted me up with remarkable strength, establishing me to his back and instructing me to keep ahold of him as we negotiated the uneven terrain. Feeling it would be somehow undignified to ride side-saddle, I elected to undo the buttons of my cassock below the waist in order to get comfortably astride the horse. (It must be a wonderfully powerful animal, for it carried both of us and my bags with no sign of fatigue.)

The sensation of riding was more foreign than I had supposed and, at first, I found it rather dizzying (I hadn’t expected to find myself so far from the ground!) Despite my inexperience, however, I felt in danger of falling only once. The animal took an unexpected swerve and my heart dropped straight down into my shoes as I nearly lost my balance, pitching dangerously to one side. At this Lord Vane scolded me for not holding onto him securely enough and, having learned my lesson, I kept my arms tight about his waist for the remainder of the journey.

As for Whithern Hall — oh, how I wish you could see it for yourself! It’s an architectural marvel. Lord Vane has proved to be as gracious a host as one could hope for, and I feel terribly silly for ever having worried about coming here.

Yours in Christ,

Fr Victor Ardelian

JOURNAL ENTRY

Dated March 1, 1950.

There is a suspicion eating away at the back of my mind, hardly credible — could this man, Lord Vane, be himself possessed by the very demon I was sent here to destroy?

There was one odd incident — in the flurry of my sudden departure from St Silvan’s Head and arrival at Whithern Hall, I had nearly forgotten it. I was in the act of passing the second of my cases to Lord Vane when his gaze fell upon the fine red lines left behind where the cat had clawed my hand in fright a minute prior. All at once his expression changed and a tigerish gleam lit his large, dark eyes.

“You’re hurt,” he said, his voice unnaturally low.

All this made me rather uneasy and I drew back a little, laughing nervously. It hadn’t seemed a very serious wound to me but I wrapped a handkerchief around the hand in question nonetheless. In another instant the look had passed and he became once again as hearty and pleasant as before. I dismissed it, thinking I must have imagined the change — yet I cannot rid myself of the memory of those eyes.

That, anyway, is when the seed of this suspicion was planted.

Night fell as we traversed the long, meandering road that skirts the edge of the lake, weaving in and out of tree and heather; climbing at last, precariously, all the way up to the manor.

I shall never forget that first sight of Whithern Hall in the gray winter twilight.

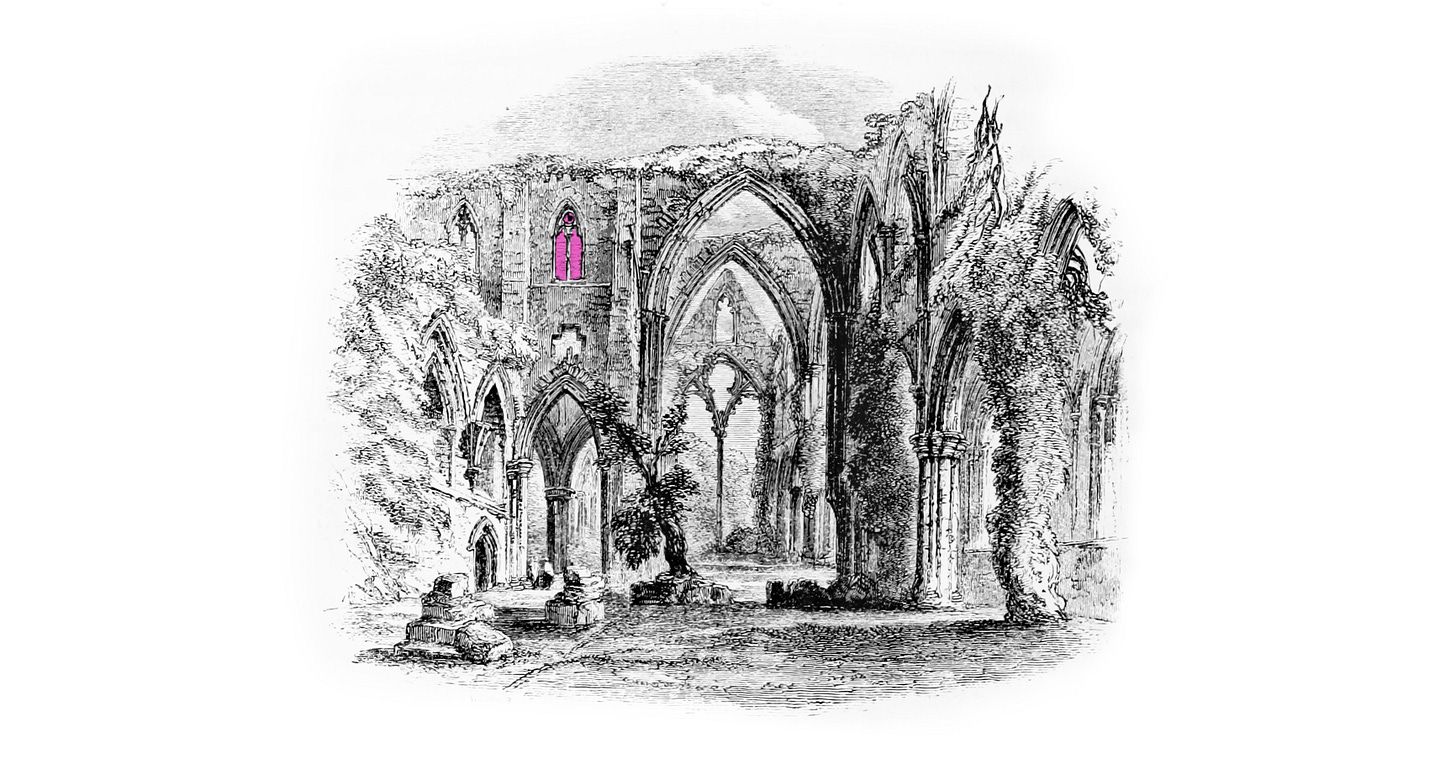

Compared to the little fishing village of St Silvan’s Head, the sheer scale of Whithern Hall is rather bewildering. Who would build such a thing, and why? What could have compelled anyone to erect an entire cathedral on this rocky, godforsaken place? For that is what greeted me as we reached the final summit — not the crumbling ruins of a modest, country church that I had imagined from Sylvia’s description, but the empty facade of a cathedral grander than anything I could have conceived. The carvings were weatherworn and broken in some places, but it was beautiful nonetheless. The intact towers loomed monumentally overhead and the hollow frame of a rose window stared down at me like the eye of God, the moon as its pupil.

Lord Vane flicked the reins and we cantered through the empty space where the enormous doors once stood, into a courtyard garden that had once been the nave. The facade was only that — a facade. The stars shone high above me as Whithern Hall itself came into view beyond; a sprawling, two-storey medieval manor house of slate-grey stone, it has been transformed by centuries of sea air, leaving it covered in streaks of dark and light.

Lord Vane seemed entirely of a piece with the place — like one of the carvings that lined the walls come to life. I studied him as he dismounted in a graceful, athletic movement, as if I could confirm my suspicions about him with a glance. He did not bear any of the traditional signs of demoniacal possession. He was not deprived of speech or sight, he did not rave or froth or gnash his teeth. Far from it — while there was a certain unearthliness about him, he did not look at all sickly. He is, in fact, in remarkably good shape, and cuts a dashing figure.

He turned and reached up to me, hands steady about my waist as he helped me back down to earth. His grip lingered absently a moment as I found my feet, and I confess I found his presence affecting.

“The cathedral was built by my ancestors around the turn of the twelfth century,” he said, mistaking the direction of my gaze. “Though the holy ground it was built on is far more ancient than that, and you’ll find the remains of other structures nearby. After the Romans invaded, it became something of a pilgrimage destination for the newly Christian Empire. Some of the original pre-Christian ruins still survive in the caverns beneath Whithern Hall.”

Against my better judgement, I was snared. “Indeed? How old are these ruins?”

Lord Vane’s laugh was rich and melodious. “Even older, I suspect, than would be wise to guess at. The very land of this place was shaped by the ancient peoples that lived here, you know — if you climb the church towers, you’ll be able to see it. It spirals subtly but visibly outward from the lake that lies between here and the village.”

“Does it really?” My voice held a quiver of excitement I wish I could have suppressed. “How remarkable that the Church was able to sanctify such a place. What kind of rituals do you think were performed here, by the ancient cult who once occupied it?”

“I hardly like to say, Father,” he said. “Perhaps I’ll show you the ruins that lie beneath Whithern Hall so that you may draw your own conclusions.”

I blushed, then, feeling I’d crossed a line into some dangerous territory. “Oh, I’m not sure that will be necessary.” I thought it wise to change the subject. “You must be a devout man,” I said — (Lord forgive me for the falsehood.)

Sadness, I thought, touched his eyes for just a instant. Something new, not unlike piety, had entered his demeanor, but it was undermined by that persistent, dark halo about him. The combination, I found, transfixed me. “Must I? Perhaps so. But don’t let me lecture you on ancient history, Father. Come, I must begin to make up for my failure as a host!”

“Oh, it wasn’t so bad as all that,” I said, following him inside. I felt compelled to reassure the man after having provoked that strange, momentary sorrow.

He brightened as we entered, though I’m not sure if it was my words that caused the change. “Let me show you to your room. You need time to rest before dinner.”

I could tell at once that Whithern Hall had been built and added to gradually over the centuries — within it is a verdant admixture of architectural eras. While the side of the house that faces the ruined cathedral has the appearance of having been added to in the seventeenth century at the earliest, the hall which I then stepped into appeared to be fully mediaeval. The walls were covered in faded paintings, hollowed out by time like ghosts.

Beyond the hall, we passed into a series of long, mazelike corridors, but Lord Vane led me swiftly through them. Perhaps I had been mistaken before about his nature, for now he seemed bright and cheerful to me, even luminous. I found his presence comforting as he took me through the treacherous beauty of Whithern Hall, up three flights of stairs and ever onward to the east, where the windows looked out over the clifftop onto the waves crashing far below.

The chamber he at last led me to was larger than many entire homes I have been in. Over the luxuriously-appointed bed there hung a canopy of deep scarlet — one which matched the curtains by the window overlooking the sea. A faint scent of some curious perfume lingered in the air.

“I hope it’s to your liking,” said Lord Vane.

“I could hardly ask for better.” Unexpectedly, despite my disorientation, I found I meant it.

“You’ll want some time to rest and get your bearings, so I shall leave you now until dinner.” He turned, then, with a courteous inclination of the head, and lifted my hand.

Then, to my surprise, he pressed it to his lips — and though it is not unheard of for laity to greet the clergy thus, I don’t believe any of the faithful have ever bestowed a kiss quite like that one on me before. I felt moved by an emotion I have no words to describe — one which I can only attribute to the pall of evil. My heart raced alarmingly, the sensation almost more than I could bear.

Then, mercifully, he released my hand and righted himself, taking leave of me with a smile.

While my suspicions grow, I must study him further before I take any definite steps.

P.S. FROM 2024:

Hello! 👋 What you’re reading is a draft version of What Manner of Man. This is the point at which the final version of the novel begins to significantly diverge from the draft you are currently reading! The conversation that takes place in this chapter is completely rewritten (and better) in the final edition, and the scene is extended into a new moment where Lord Vane and Father Ardelian visit the stables. Plus there’s more of Father Ardelian’s thoughts on demons, and some blasphemous theology!

(You can get the complete, edited and expanded novel DRM-free on Itch.io or at the retailer of your choice.)

Are you enjoying What Manner of Man? Are you curious about what things Lord Vane and Father Ardelian might be getting up to that our priest isn’t bothering to write down? How about what Sylvia and Danny think of all this?

I’m excited to announce that, starting today, Patreon supporters of Accomplice tier and upward will be getting exclusive access to an occasional series of short, post-chapter vignettes — fluffy, spicy, or funny moments that don’t quite fit anywhere in the text. Each will be unedited and under 1000 words (probably.) The short for this chapter is already live as of this email.

A taste:

My legs burned with every stair. The cathedral’s eastern tower was even higher than it looked. If there had been any doubt in my mind when Lord Vane had said this was the highest point on the island, it had been long since been incinerated by the fire in my muscles.

I hope you enjoy it! :)

-St John

I've decided that Father Ardelian can't have Lord Vane because I want him

Comparing the two ways Ardelian wrote about meeting Vane is going to be fun.

I also like seeing various Dracula parallels and how the differences show that these are going to be very different stories. Dracula was indirect and forceful with bringing Jonathan to the castle, doing so incognito as a coachman. Vane brings Ardelian to the manor as himself and with Ardelian riding on the same horse. Dracula would have killed Jonathan over the shaving cut if it weren't for the crucifix, Vane has much more self control.